Bronx Building Collapse: Legal Guide Under New York Premises & Municipal Liability

- Reza Yassi

- Oct 3

- 27 min read

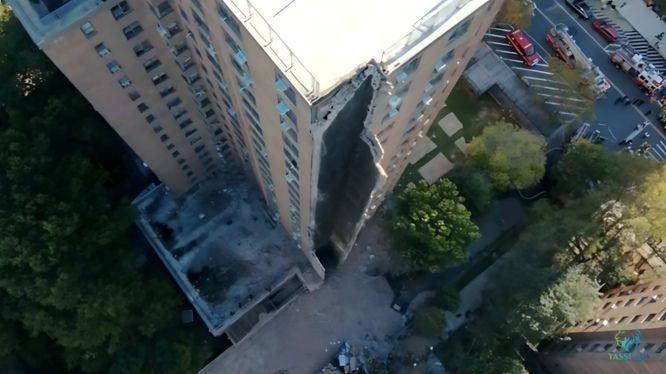

On the morning of October 1, 2025, a gas explosion rocked a 20-story public housing apartment in the Bronx, causing a partial building collapse at the NYCHA-owned Mitchel Houses (abc7ny.com). Miraculously, no injuries or deaths were reported, as tons of brick and debris from a collapsed chimney shaft rained down near a playground and schoolyard. City officials called it a narrowly averted “major disaster”. For the residents of New York, this event entails equally compelling questions: Who has the responsibility if a building collapses? What law governs the duty of landlords, contractors, building owners, and the city to avoid losses? And if somebody is injured, what do they do immediately to protect their health and rights?

Aerial view of the Bronx apartment building after the explosion, with an entire corner chimney structure collapsed down the 20-story facade (FDNY drone image). This October 1, 2025, incident highlights the importance of New York’s premises liability and municipal liability laws in building collapse cases.

In this blog, we focus exclusively on New York law – particularly NYC’s premises liability and municipal liability framework – as it applies to building collapses. We'll discuss the legal obligations of property owners and public entities, review important statutes and case law, assess high-profile structural failures in NYC's past, and lay out procedural obstacles (such as the doctrine of prior written notice and the notice of claim process) to a lawsuit against the city. Most importantly, we provide practical advice for all persons who suffer injury as a result of a building collapse, show you what medical steps to take immediately after the collapse, tips for documenting the injury, and when you should contact the appropriate legal representation.

We’ll also suggest some educational TikTok video ideas, social media content, SEO keywords, and outreach strategies to help inform the public about their rights after such disasters. Accuracy, legal credibility, and real utility to potential clients are our top priorities in this marketing plan and legal guide.

Legal Framework: Premises Liability in NYC Building Collapses

Premises liability is the area of law holding property owners and occupiers responsible for accidents caused by dangerous conditions on their property. In New York, landlords and building owners owe a duty of reasonable care to keep their premises safe for tenants, visitors, and the public. Unlike some states, New York no longer differentiates between “invitees” or “licensees” – since the landmark case (Basso v. Miller (1976)), owners must exercise reasonable care under the circumstances for all lawful visitors. For a building collapse scenario, this means property owners can be liable for collapse-related injuries if their negligence in maintaining the building contributed to the disaster. Below, we break down the key obligations and liability considerations for the various parties involved:

Landlords & Building Owners: New York law imposes an affirmative duty on landlords to maintain their buildings in a safe condition. This duty is codified in both state and city law. For example, N.Y. Multiple Dwelling Law §78(1) mandates that “Every multiple dwelling, including its roof and every part thereof, shall be kept in good repair,” and explicitly states “the owner shall be responsible for compliance”. Likewise, the NYC Building Code (Administrative Code §28-301.1) provides that “All buildings and all parts thereof shall be maintained in a safe condition… The owner shall be responsible at all times to maintain the building and its facilities… in a safe and code-compliant manner.” In short, NYC landlords have a non-delegable duty to keep the premises safe and address structural hazards. Failing to repair known structural defects (or ignoring required maintenance of boilers, gas lines, walls, etc.) can make an owner liable for resulting injuries. Notably, this statutory duty expands the common-law obligations of out-of-possession landlords: even areas within a tenant’s apartment can implicate the owner if a duty to repair is imposed by law or lease. In collapse cases, an owner’s negligence might include shoddy maintenance, ignored warning signs (like cracks or leaks), or violations of safety codes. If an investigation finds that the Bronx explosion and collapse resulted from deferred maintenance or code violations (for instance, a faulty boiler that should have been repaired), the building owner (here NYCHA) could be on the legal hook for negligence. Owners are expected to have regular inspections and comply with all building safety regulations, including hiring licensed professionals for gas and boiler work. Failure to do so not only risks civil liability but can even lead to regulatory fines or criminal charges in egregious cases.

Contractors and Maintenance Companies: Construction and maintenance contractors working on the premises also carry responsibility for safe building conditions. If a contractor’s negligence contributed to a collapse (for example, improper installation of a gas line or structural supports), they can be held liable alongside the owner. New York law permits injured parties to bring third-party negligence claims against contractors who created or failed to correct a dangerous condition. In practice, courts will consider the contractor’s control over the work and whether the hazard was foreseeable. A dramatic illustration is the 2015 East Village gas explosion, where a landlord and her plumber illegally tampered with gas lines; this caused a massive blast that leveled multiple buildings. Those individuals were later convicted of manslaughter and other charges for their roles in the deadly explosion (abc7ny.com). While that was a criminal case, the same underlying negligence (an illegal, substandard gas hookup) would make the landlord and contractor civilly liable for the resulting injuries and deaths. In the Bronx collapse scenario, if reports confirm that work was being done on the boiler at the time of the explosion (apnews.com), investigators will scrutinize the contractors involved. Any contractor who failed to follow proper procedures or violated safety codes (such as not properly venting the boiler or mishandling gas lines) could face liability. Contractors in New York are expected to adhere to all applicable building codes and industry standards; deviation from those can be used as evidence of negligence. Additionally, maintenance companies hired via NYCHA’s privatization initiatives could share liability if they were responsible for upkeep of the boiler or chimney and neglected it. In sum, all parties who had a hand in the building’s maintenance or recent work may be part of a collapse lawsuit, depending on their fault.

Tenants: What about tenants themselves? Generally, tenants are not liable for structural issues unless they caused them through some unusual misuse. New York’s Multiple Dwelling Law §78 does note that a tenant can be liable for a violation caused by the tenant’s own willful act or negligence. For instance, if a tenant illegally stored explosive materials that caused a blast, they could be liable. But an ordinary resident has no duty to repair structural elements; that duty rests on the landlord. Tenants do, however, play a role in reporting hazards. From a liability standpoint, if tenants previously complained about gas odors, cracks, or other dangers and those warnings were ignored, it strengthens the negligence case against the owner (showing the owner had notice of the problem). In any event, injured tenants would be plaintiffs, not defendants, in a building collapse case, barring highly unusual circumstances.

Utility Companies: In cases where gas, electric, or water infrastructure defects cause or contribute to a collapse, the relevant utility company might be implicated. For example, Con Edison (the local gas utility) was found partly at fault by the NTSB for the 2014 East Harlem gas explosion that destroyed two buildings, due to a defective gas pipe fusion joint it installed (abc7ny.com). In that incident, a cracked gas main (combined with a sewer leak) led to a horrific explosion that killed 8 people and injured dozens (abc7ny.com). Con Ed ultimately reached a $153 million settlement for that disaster (reuters.com). Utilities are subject to state and federal safety regulations; if their negligence in maintaining gas lines or responding to leak complaints causes a building to blow up or collapse, they can be held liable. In the Bronx collapse, Con Ed’s role is under scrutiny – they did shut off the gas post-explosion (abc7ny.com), but it’s not yet known if any prior gas leak reports or utility negligence was involved. Generally, utility liability hinges on notice as well – e.g., whether the company had been alerted to a gas leak and failed to act. We mention this because while our focus is premises liability (landlord/municipal law), real-world collapse cases often have multiple layers of fault, including utilities.

In New York premises liability cases, proving the owner or contractor’s negligence usually requires showing they had “notice” of the dangerous condition. This can be actual notice (they knew about a structural defect or code violation beforehand) or constructive notice (the problem existed long enough or was so obvious they should have known). As one defense firm noted, to establish a landlord’s liability for a defect, a plaintiff must show duty, notice, and an opportunity to repair (“access”). If a landlord can prove that they had no knowledge of a latent structural flaw (and no reason to know of it despite inspections), they might avoid liability. However, building collapses are rarely completely out of the blue – there are often warning signs (even if only discovered in hindsight). For instance, with a boiler explosion, there might have been prior malfunctions, smells, or a failed inspection. In litigation, tenants’ prior complaints, building inspection records, and maintenance logs become critical evidence. New York law (including the NYC Housing Maintenance Code) requires landlords to address tenant maintenance complaints; a paper trail of ignored complaints strongly bolsters a victim’s case. In the Bronx case, news reports already noted that the building had a partial stop-work order since June 25, 2025 (abc7ny.com) – suggesting there were known issues being addressed (or not addressed) before the collapse. Such facts would be explored to determine if NYCHA knew of a hazardous condition (like a faulty chimney or boiler) and failed to fix it in time.

Finally, New York allows injured parties to use negligence per se in some situations – meaning a violation of a safety law or code can automatically establish the duty and breach elements of negligence if the law was meant to protect the class of persons and harm that occurred. Building code violations, however, must be specific to serve as a predicate for liability. Courts have held that general provisions like “maintain a safe building” (e.g., Admin. Code §§ 27-127, 27-128, predecessor to §28-301.1) are too general to form a negligence per se basis newyorkappellatedigest.com – instead, one must fall back on common-law negligence standards. More specific code violations (for example, failing to install required safety devices or violating a detailed engineering requirement) can strengthen a case. In a collapse scenario, an expert engineer would inspect the wreckage for code violations (perhaps an improper removal of a load-bearing wall, or an uninspected boiler). A proven code breach can not only prove negligence but might also allow punitive damages if the conduct was grossly negligent or illegal (as seen with the East Village gas case, where the conduct led to criminal convictions (abc7ny.com).

Key takeaway: In NYC, landlords and building owners bear primary responsibility for preventing building collapses through diligent maintenance and code compliance. If they drop the ball, the law is poised to hold them accountable for injuries. Contractors and others involved can share liability if their negligence is a factor. The legal framework is designed to incentivize property owners to fix problems before they turn into catastrophes – because after a collapse, saying “we didn’t know” is often not an adequate defense if the danger was knowable with proper care.

Municipal Liability: City Obligations and Immunities in Structural Collapses

When a private building collapses, the city’s role might only be as regulator (e.g., did the Department of Buildings properly inspect or enforce codes?). But in many cases – including the Bronx collapse – the City of New York is itself the property owner or manager. The Bronx high-rise that partially fell is part of NYCHA (New York City Housing Authority), a city agency and the largest public housing operator in the country (apnews.comapnews.com). This raises the issue of municipal liability: can the City (or NYCHA) be held liable like a private landlord, and under what conditions can the City be sued for a collapse?

City as Landlord vs. City as Regulator

New York law draws an important distinction in municipal liability cases: was the city acting in a proprietary capacity (performing duties that a private entity could perform, like being a landlord), or in a governmental capacity (exercising its governmental functions like inspections or emergency services)? If the City is acting as a proprietary property owner, it is “subject to ordinary tort liability” under the same principles as any private landlord. In other words, NYCHA must maintain its buildings safely just like any landlord, and if it negligently fails to do so, it can be liable for injuries. The law will not grant NYCHA immunity simply because it’s a city agency when it comes to its landlord activities. In fact, courts have explicitly held that when a municipality engages in conduct that substitutes for or parallels a private sector service (like providing housing), it will be treated as a landlord and judged by ordinary negligence standards. So, if a NYCHA building collapses due to poor maintenance, the City’s liability is analyzed like that of any property owner: did it know or should it have known of the hazard, and did it act with reasonable care to fix it? There are many examples of NYCHA being sued for premises injuries (e.g., ceiling collapses in apartments, elevator accidents, etc.,) and the key issues are typically notice and negligence, not governmental immunity. For instance, in a recent premises liability case against NYCHA, the court dismissed the claim only because the tenant could not prove NYCHA had actual or constructive notice of the defect – reinforcing that if notice were proven, NYCHA could indeed be held liable.

By contrast, when the City is performing governmental functions, it has special protections. Building inspections and code enforcement are classic governmental functions. Generally, a city (through its Department of Buildings inspectors) cannot be held liable for negligence in failing to inspect a private building or for issuing permits/code approvals, unless a special duty is established. New York’s doctrine of “special duty” (or special relationship) requires a plaintiff to show that the municipality, through direct contact or promises, assumed a specific duty to them beyond what is owed to the public at large. This is a high bar. For example, if a city building inspector negligently signs off on a structure that later collapses, victims usually cannot sue the City for that, because enforcing building codes is a public function owed to everyone, not a specific assurance to those individuals. Additionally, municipalities have immunity for discretionary acts, meaning if an official had to exercise judgment (like whether to issue a permit or how to conduct an inspection), the city can’t be sued for those decisions (law.justia.com). The idea is that fear of lawsuits shouldn’t deter officials from making judgment calls in governance. In a noteworthy case, homeowners sued NYC after a retaining wall collapsed on their homes, alleging the Department of Buildings negligently approved and inspected the development. The court held the City had “absolute immunity” for discretionary permitting and inspection decisions, and the plaintiffs failed to show a special duty to them specifically (law.justia.com). This demonstrates the uphill battle when trying to pin liability on the City as regulator rather than as owner.

Applying these principles to building collapses: If the Bronx collapse had occurred in a privately-owned building, victims might consider suing the City for failing to prevent it (perhaps by missing violations or not conducting timely inspections). However, such a claim would likely fail absent extraordinary facts, because building oversight is governmental. Only if the City had undertaken a specific duty – say, an inspector explicitly told a tenant “don’t worry, it’s safe” after complaints, creating reliance – might a special duty arise. Conversely, in the Bronx case the City is the landlord (NYCHA), so the City’s duty is the same as any landlord’s duty to maintain the building safely. Governmental immunity won’t shield NYCHA from a negligence claim about maintenance because that’s a proprietary function. (NYCHA might try some defenses unique to public entities, but generally they’re held to ordinary negligence standards in maintaining housing.)

One caveat: even when acting as a landlord, a municipality like NYCHA still enjoys certain procedural protections, which we discuss next (notice of claim, etc.). But when it comes to fault, New York courts do not let the City off the hook simply because of its governmental status if the City was essentially a negligent property manager. As the Court of Appeals has said, a municipality is liable in its proprietary capacity when performing “services that traditionally have been supplied by the private sector,” and it will be held to the “same duty of care as private individuals and institutions engaging in the same activity”. Providing safe housing is one such activity.

Prior Written Notice Doctrine (When Suing NYC for Hazardous Conditions)

New York’s prior written notice law is a procedural hurdle that often comes up in municipal liability cases. Certain NYC laws (and state law general provisions) require that, before you can sue the City for injuries caused by dangerous conditions on public property, the City must have had written notice of the specific defect in advance. This rule most commonly applies to things like sidewalk defects, potholes, or roadway hazards – a plaintiff must prove the City was notified in writing of the dangerous condition (e.g. a pothole or broken sidewalk) at least some days before the accident, or else the case is barred. NYC Administrative Code §7-201 (the “Pothole Law”) embodies this for streets and sidewalks, reflecting the idea that a city can’t fix problems it’s unaware of. There are only two narrow exceptions to the prior written notice requirement: if the City affirmatively created the hazard through negligence, or if the hazard was caused by a “special use” of the property that benefited the City. Simply claiming the City “should have known” (constructive notice) is not enough – absent written notice or these exceptions, the City isn’t liable.

How does this doctrine affect building collapse cases? If the collapse involves City-owned property (like NYCHA), the prior written notice law per se might not strictly apply as it does to sidewalks (the law names streets, sidewalks, etc., not buildings). However, as a practical matter, a similar concept holds: the City is generally not liable for dangerous conditions on its property unless it had notice of them. In a premises liability case against NYCHA or the City, a plaintiff must show the City knew or should have known of the structural defect (actual or constructive notice) and failed to repair it. While you might not need written notice filed with the City (unless it’s the kind of hazard covered by the statute), proving some form of notice is crucial. For example, if NYCHA received multiple repair tickets about shaking pipes or cracks in the boiler room prior to this explosion, that would count as actual notice of a hazard. If the condition (like a deteriorating chimney structure) was visible and existed for a long time, NYCHA could be deemed to have constructive notice. On the other hand, if an unknown latent defect (say, a hidden manufacturing flaw in the boiler) caused the explosion with no prior warning signs, NYCHA might argue it had no notice and thus no opportunity to fix it – potentially avoiding liability.

The prior written notice doctrine proper would likely come into play if someone injured by the collapse sued the City for a related sidewalk or street condition – for instance, if debris from the collapse had previously fallen and injured someone on the sidewalk due to an unrepaired facade. In such a case, NYC’s defense could be: “We had no written notice of the facade defect endangering pedestrians.” A real-world parallel is the 2019 Midtown facade collapse that killed architect Erica Tishman. It was revealed that the building owner and the City knew for months that the facade was crumbling – the City had even issued a violation to the owner for it, but neither the owner fixed it nor did the City erect a sidewalk shed in time. After Tishman’s tragic death from falling masonry, the City was criticized for not following up more aggressively. Her family’s wrongful death lawsuit against the building owner also initially named the City for failing to protect pedestrians. The City’s typical response in such suits is to deny liability, citing lack of a special duty and (implicitly) that enforcement actions (issuing a violation) are discretionary. Indeed, reports noted that the City argued the victim herself might have been at fault, deflecting from its own lapse (nbcnewyork.com). Ultimately, the building owners were criminally charged for the facade failure, underscoring that primary blame lies with the owners. The City’s liability would hinge on whether it had an obligation to do more once it knew of the danger. Generally, unless the City’s conduct was egregious or it undertook to direct fix/maintenance (which would be proprietary activity), it is tough to sue the City for failing to prevent a private building’s collapse.

In summary, New York’s municipal liability framework means that if you aim to sue the City of New York for a building collapse, you must navigate both the notice requirement and the governmental immunity issue. If the City is the landlord (as with NYCHA), you focus on proving negligence like in any landlord case (with notice of defect, etc.), but you also must follow special procedures like the notice of claim (discussed below). If the City is merely the regulator, it is largely immune absent special circumstances. And if the hazard was on public property (like debris on a public sidewalk), the prior written notice rule could bar the claim unless the City had been formally warned of that specific hazard or caused it. The policy behind these rules is to give municipalities a chance to fix problems and to shield them from overwhelming liability, but from a victim’s perspective, it means an extra layer of proof is required compared to suing a private party.

Special Procedural Considerations: Notice of Claim and Deadlines

Anyone injured due to a building collapse who plans to bring a claim against a municipal entity (be it the City of New York, NYCHA, or another city agency) must be aware of strict procedural rules. New York law requires filing a Notice of Claim with the City within 90 days of the incident as a prerequisite to suing a municipality (General Municipal Law §50-e). This is separate from the prior written notice of defect discussed above – the notice of claim is essentially informing the City that you intend to seek damages for a specific incident, so the City can investigate and potentially settle. In the context of our Bronx collapse, if someone were injured and wanted to sue NYCHA/City, they would need to file a Notice of Claim within 90 days of October 1, 2025. Failure to do so can result in dismissal of the lawsuit. The notice of claim must set forth the basic facts of the claim – when, where, and how the injury occurred, and that you’re claiming the City’s negligence caused it. NYC has made this relatively convenient through the Comptroller’s Office (claims can be submitted in person, by certified mail, or even electronically via the eClaim system). After filing the notice, the claimant must then wait at least 30 days and can then commence a lawsuit (and the lawsuit against a city must usually be filed within 1 year and 90 days of the incident, per GML §50-i, unless wrongful death, which has different rules).

For example, in a ceiling-collapse injury case in a NYCHA apartment, the tenant would file a notice of claim with the NYC Comptroller detailing the incident. The City might conduct a hearing (a “50-h hearing”) to gather information. Only after that can the tenant file the formal lawsuit. Compliance with these steps is crucial – they are often pitfalls for the unwary. Our firm (in this hypothetical marketing context) would immediately assist a new client in preparing and filing the notice of claim to preserve their rights.

It’s worth noting that filing a notice of claim is not required for suing private landlords or contractors – it’s only for public entities. So if your case involves both NYCHA and a private maintenance contractor, you must do the notice of claim for the NYCHA part, but you can proceed against the private party on the normal timeline (3-year statute of limitations for personal injury in NY). Still, as a practical matter, you’d usually pursue all defendants in one action, so the strictest timeline (the City’s) dictates your early actions.

One more procedure: prior written notice vs notice of claim – don’t confuse the two. Prior written notice (discussed earlier) is evidence that you must have that the City knew of a defect; the Notice of Claim is a document you serve on the City after you were hurt. Both are unique wrinkles in municipal cases. To recap: an injured person should (a) file a notice of claim within 90 days, and (b) gather any proof that the City had notice of the dangerous condition before the collapse (for instance, tenant complaints, violation reports, or maintenance records). The union of those two “notices” strengthens the case.

Comparing High-Profile NYC Structural Collapse Incidents

New York City has, unfortunately, seen several major structural failures and collapses over the years. Each incident provides insights into how the law assigns liability and what changes follow. Here we briefly compare a few notable cases to the Bronx collapse:

2015 East Village Gas Explosion: This was a harrowing case where an illegally tapped gas line caused an explosion that leveled three buildings on Second Avenue((abc7ny.com)). Two people (a restaurant patron and a worker) were killed, and at least 13 were injured. Investigations revealed the building owner and her contractors had bypassed the gas meter to steal gas, and had months earlier been warned by the utility about ga as odor. The legal outcome was dramatic: the owner, an unlicensed plumber, and a general contractor were all convicted of manslaughter and criminally negligent homicide in 2019(abc7ny.com). From a civil liability perspective, this case was straightforward negligence (even gross negligence) by the owner and contractors – a textbook example of landlord responsibility for a collapse. There was no question of City liability here, except perhaps scrutiny on how the Buildings Department missed the illegal setup. The case underscored that expedience and profit at the expense of safety will be punished severely(abc7ny.com). It likely prompted stricter utility inspections and harsher penalties for code violations. A key takeaway: if an investigation finds reckless or illegal practices behind a collapse, expect not only civil suits but also possible criminal charges in NYC. The Bronx collapse so far does not appear intentional or due to malfeasance; early info suggests it might relate to a boiler accident on the first day of heating season(abc7ny.com). But if, hypothetically, someone had bypassed safety controls on that boiler, the East Village case shows how the law would respond.

2014 East Harlem Gas Explosion: This tragedy involved public infrastructure failures. A gas leak led to an explosion that obliterated two apartment buildings in Harlem (Park Avenue and 116th St), killing 8 and injuring about 70 (en.wikipedia.org). The NTSB investigation found fault on both Con Edison and the City – a defective ConEd-installed plastic pipe joint, and a neglected city sewer line that had been leaking and eroding soil, which likely caused the gas main to crack(abc7ny.com). Essentially, ConEd and NYC DEP (Department of Environmental Protection) each had prior notice of problems (ConEd knew of previous gas leaks; the City had a report of a sewer break since 2006), but neither acted adequately(abc7ny.com). Legally, the victims had grounds to sue both the utility and the City. In fact, Con Edison settled for $153 million with victims (reuters.com). The City’s liability would hinge on the prior written notice rule and negligence – here, the City did have actual notice of the sewer issue for years and didn’t fix it(abc7ny.com), which is a strong case of city negligence in a proprietary way (maintaining sewers). This event led to improved coordination between utilities and the City on underground infrastructure. It shows that in some collapse scenarios (especially gas-related), multiple defendants (public and private) can share liability. The Bronx case, being NYCHA, similarly could involve multiple defendants (NYCHA, possibly contractors, perhaps ConEd if a gas leak is implicated). Courts would apportion fault based on each’s contribution to the hazard.

2023 Lower Manhattan Parking Garage Collapse (Ann Street): In April 2023, a 98-year-old parking garage suddenly pancaked, killing the garage manager and injuring five employees(abc7ny.com). The cause, as a subsequent investigation revealed, was egregious engineering negligence: the private garage owner and their engineers had identified a cracked support column, but instead of proper repair, a handyman was removing bricks from a load-bearing pier without realizing those bricks were holding the building up(abc7ny.com). When critical bricks were taken out, the structure gave way(abc7ny.com). No city inspectors were directly involved at the moment (though one could ask if DOB should have flagged the deteriorated condition earlier). The report squarely blamed the garage owner and the engineering firm for a chain of preventable errors(abc7ny.com). Because those mistakes were “proprietary” actions (building maintenance), the owners and engineers face liability – indeed, a lawsuit was swiftly filed (e.g., the family of the deceased manager retained counsel to sue). The City responded by launching a sweeping review of older parking structures(abc7ny.com), showing how a collapse can prompt regulatory action even if the City isn’t liable for the one that happened. The lesson: poor maintenance and DIY repairs in aging structures can be catastrophic, and property owners will be held responsible for not hiring qualified professionals. The Bronx tower that partially collapsed is also an aging structure (built in 1966(abc7ny.com)), and NYCHA’s portfolio is full of buildings from the mid-20th century with deferred maintenance (apnews.com). If the cause traces back to “human errors” like in the garage case, those humans (and their employers) will bear the legal blame. Notably, in the garage case, no criminal charges were brought (authorities deemed it negligence but not rising to criminal intent)(abc7ny.com) – but civil liability is almost certain. The Bronx incident will similarly be parsed: was it a maintenance error, an inspection oversight, or an unavoidable accident? Each scenario points the finger differently.

2019 Midtown Facade Collapse (Falling Debris): We touched on this earlier – a piece of a building’s facade fell and killed a pedestrian on a Manhattan sidewalk. The building owner had been cited for façade issues, but delayed repairs. This case highlights NYC’s Local Law 11, which requires regular facade inspections for buildings over six stories. The legal outcome saw building owners facing criminal charges for neglect, and the victim’s family suing for wrongful death. The City quickly required immediate sidewalk sheds at hundreds of buildings with outstanding facade violations after this incident. It underscores that NYC has specific safety laws (facade inspections, etc.) and when those are flouted, liability is clear. In a collapse scenario, one should check if any local laws (e.g., requirements for boiler inspections or gas piping inspections per Local Law 152) were not followed by the owner. Non-compliance can be a smoking gun in establishing negligence.

Each of these incidents reinforces a few principles: (1) Negligence will eventually come to light – whether it’s a landlord’s illegal shortcut, the city’s overlooked infrastructure, or an engineer’s blunder, investigations in NYC are thorough and tend to assign cause. (2) Liability follows control and knowledge – the party that had control over the hazard and knowledge (or notice) of the risk is usually held liable. (3) High-profile collapses often lead to changes – either in enforcement or new laws – aimed at preventing repeat tragedies. For example, after a crane collapse in 2008, NYC tightened crane inspection rules; after the East Village explosion, gas line inspection and certification rules were toughened. We may see, in the wake of the Bronx collapse, renewed scrutiny of NYCHA’s aging infrastructure (half a million New Yorkers live in NYCHA housing, apnews.com) and perhaps accelerated capital repairs or monitoring of boiler systems.

For potential clients or affected residents, these comparisons show that you are not alone – unfortunately, others have suffered from structural failures, and the law has pathways to hold wrongdoers accountable. Whether it’s a private landlord or the city housing authority, New York’s legal system provides recourse to seek compensation and force changes that improve safety.

What To Do If You’re Injured in a Building Collapse (Medical and Legal Steps)

Suffering injuries in a building collapse or explosion is a frightening, chaotic experience. It’s important for victims to prioritize health and safety, while also laying the groundwork for any future legal claim. Here is a step-by-step guide with actionable medical and procedural advice for anyone injured in such an incident:

1. Get to Safety and Seek Immediate Medical Attention. Your life and health come first. In the moments after a collapse, you may be disoriented – follow emergency responders’ instructions to evacuate the area or find a safe zone. If you’re trapped, try to stay calm and attract attention (e.g., call 911 if possible, yell, or tap on surfaces). Once clear of danger, get medical help even if you think you’re “okay.” Collapses often involve dust inhalation, hidden internal injuries, or adrenaline-masked pain. Let paramedics examine you on-site; if they recommend hospital evaluation, go with them. Prompt treatment not only safeguards your well-being but also creates a medical record of your injuries. In New York, when you later claim injuries, those ambulance and ER reports documenting trauma from the collapse will be key evidence linking the event to your medical condition. Delaying treatment can not only worsen injuries but also give insurance companies an argument that “it must not have been that serious.” So, when in doubt, get checked out. Concussions, spinal injuries, or crush injuries might not be obvious in the first hour but can be life-threatening. Furthermore, from a legal perspective, having a continuous treatment record from the day of the collapse forward strengthens your case.

2. Contact Authorities and Report Your Injuries. In a major incident like an apartment building collapse, authorities will likely already be on scene (FDNY, NYPD, OEM, etc.). Make sure to give your name to responders and report that you were injured. This ensures you are included in any official incident reports. If you’re a tenant or resident, also notify your landlord or building management in writing as soon as practical that you were injured and where it happened. In the case of NYCHA, for example, you’d file an incident report with the development’s management office. This creates a formal record. If the building collapse was less high-profile (say, a partial collapse of a ceiling or balcony), calling 311 or the Department of Buildings to report the hazard is also a wise step (after emergency needs are met). The City might send inspectors, and their violation report could serve as evidence of the dangerous condition. In summary, ensure the event and your injury are documented by the proper authorities.

3. Document the Scene and Your Injuries (if you can do so safely). Physical evidence can decay or be cleaned up quickly after a collapse, so if you are able and it’s safe, gather evidence as soon as possible. This includes photographs or video of the collapse scene: debris, structural damage, and any obvious causes (e.g,. a burst pipe, a dislodged boiler, etc.). Many times, your smartphone photos could later provide crucial clues – for instance, capturing a failed bracket or a cracked beam among the rubble. If you’re a resident, photograph the condition of your apartment or belongings too. However, only do this if you are not jeopardizing your safety or interfering with rescue operations. Often, the area will be cordoned off; you might take photos from outside the tape if allowed. Also, get pictures of your injuries (cuts, bruises, casts, etc.) and keep records of all medical treatment (hospital discharge papers, prescriptions, etc.). Visual evidence is powerful: as one legal resource notes, photos and videos of the accident scene and your injuries provide “irrefutable proof” of what happened. If you are too injured to do any of this, you can ask a trusted friend or family member to help gather evidence in the days following the incident. Additionally, keep any physical evidence – for example, the dusty or bloodied clothes and shoes you were wearing (don’t wash them). They might later be shown in court to demonstrate the force of the collapse or the environmental hazards you endured.

4. Identify Witnesses and Other Victims. In a building collapse, you are likely not alone – other tenants, neighbors, or passersby may have seen warning signs or have information. If you can, get the contact information of anyone who witnessed events leading up to or during the collapse. Fellow residents might tell you, “I smelled gas for hours before,” or “I saw construction work happening without proper support.” These details are invaluable. Get names, phone numbers, or emails of witnesses. If you spoke to any officials or inspectors prior to the incident (e.g., you had previously complained to a NYCHA repair hotline or a super about a crack or smell), note those communications and who was involved. All of this can help your attorney later establish notice and causation. Also, stay in touch (to the extent comfortable) with other victims – there may be a class action or group effort, or at least they can corroborate your account that, say, “everyone on the 5th floor felt shaking for days prior.” New York law allows consolidation of cases or class actions when multiple people are harmed by the same event, so sharing information can be mutually beneficial.

5. Notify Your Insurance (If Applicable). This is more about property damage, but often in a collapse, people lose personal property or have to relocate. If you have renter’s insurance or homeowner’s insurance, report the incident to your insurer. They might cover some of your belongings or additional living expenses while you’re displaced (though they may later subrogate against the negligent party). For personal injury, if you have health insurance or Medicaid/Medicare, continue your treatment – those insurers may later assert a lien on your recovery, but your health is paramount. Do not give detailed statements about fault to any insurance (yours or others) at this stage – simply report the basic facts needed. It’s often wise to consult an attorney before giving any recorded statement to an insurance adjuster.

6. Consult a Qualified New York Personal Injury Attorney ASAP. Building collapse cases are complex and often involve governmental entities, which means tighter deadlines and special rules. An experienced New York premises liability lawyer will immediately start investigating on your behalf, preserving evidence (possibly by getting a court order to inspect the site or an engineering analysis before debris is removed), and ensuring compliance with all notice requirements. As discussed, if the City or NYCHA is a potential defendant, a Notice of Claim must be filed within 90 days. That clock starts ticking the day of the collapse, so do not delay. A lawyer will also know whom to put on notice – e.g., the NYC Comptroller for a NYCHA claim, as well as any private parties. They can also guide you on potentially available benefits (for instance, in major disasters, sometimes victim compensation funds or emergency relief funds are set up). Initial consultations are usually free, and personal injury lawyers in NYC work on a contingency fee (they only get paid out of a settlement or verdict). Hiring a lawyer does not mean you’re “suing immediately” – it means you’re protecting your rights and investigating. If you’re worried about suing your landlord (some tenants fear retaliation), remember that for public housing tenants, there are protections in place, and you cannot be evicted for asserting your legal rights to compensation for the landlord’s negligence.

7. Continue Medical Care and Follow Doctors’ Orders. This is both for your well-being and your case. Attend all follow-up appointments, therapy sessions, etc. Keep a journal of your symptoms, pain levels, and how the injuries impact your daily life. This will serve as evidence of damages (pain and suffering, lost quality of life) down the line. If you experience trauma (which is common – collapses can cause PTSD or anxiety about buildings), consider counseling; mental health injuries are compensable too if caused by the incident.

8. Avoid Social Media Pitfalls and Be Cautious with Public Comments. In today’s world, you might be inclined to post on social media about the collapse. Think twice before posting details of your injuries or blaming someone online. Those posts can and will be seen by the other side. It’s okay to mark yourself safe or express general emotions, but refrain from statements like “I’m fine, just a scratch” (when you later claim injuries) or speculating about the cause (“I always knew the landlord was cutting corners!”), which could complicate your case. Let the investigation reveal the fault. Also, the media might reach out to you since it’s high-profile – you have no obligation to speak to the press, and if you do, keep it to the facts of what you experienced. An attorney can handle press inquiries if it becomes big.

By following these steps, you protect both your health and your legal rights. Our firm’s role (if this were an actual firm blog) would be to handle the legal heavy lifting so you can focus on recovery. We would investigate the cause (often hiring structural engineers or explosion experts), identify all liable parties, file the necessary notices, and pursue maximum compensation for your injuries, medical bills, lost income, and suffering. Remember, building collapse cases often involve serious injuries – you may be entitled to recover not just economic costs but also damages for your pain, emotional distress, and loss of enjoyment of life. In egregious cases, punitive damages may be sought to send a message. The ultimate goal is twofold: secure justice and financial relief for you, and push for changes that ensure safer buildings moving forward.

At Yassi Law P.C., we provide free consultations for personal injury victims who have been injured in these types of accidents. Call today.

Attorney Disclaimer: The information provided above is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reviewing this guide does not create an attorney-client relationship. If you require legal assistance, please contact a qualified attorney as soon as possible.